A Life without Masks.

An Interview with Lourdes Grobet.

by Angélica Abelleyra

She is straightforward and fun. She sometimes becomes pensive, but then immediately gestures with her hands, livens up and once again defies the Saint of Formality–that ubiquitous incarnation of evil whom she has always managed to defeat. Her words are transparent in the same way that her creative work is a transparent and yet kaleidoscopic reflection of an eclectic, suggestive outlook on life.

Her family members were body-conscious sports lovers rather than artists. Of course, the rings and parallel bars on which she exercised helped herdefine her body, but dance–and the continuity, rhythm and sensuality of movement–was the medium that showed her the path to creativity. The kind of creativity that was not fostered in her home, where there was indeed no library or, for that matter, encouragement from her parents when she showed them her disproportionate drawings as a child; the kind of creative universe she did not find in Catholic schools but that she would fortunately become aware of after breaking out of the social and religious environment in which she had been brought up.

–Without motivation at home, how did you develop a passion for art?

–Art and my need to get to know what's around me are things I have been concerned about since I was a child. At home there wasn't much motivation to pursue art but my parents were very open socially. My father was Swiss and didn't have class prejudices so that allowed me to meet all kinds of people. He had a plumbing business; he was so close to his plumbers that we sometimes all ate at the same table. We did start having problems when I wanted to go to wrestling matches, since he didn’t think that was the kind of thing women should see. He didn't want us to become friends with the "bums" in the ring or in the audience. That was something I never understood, but I never confronted him about it.

Dance was my initiation into art. There was a harmony in dancing that I needed to complement the brusque movements of gymnastics. Rhythm has been an indispensable part of my life; I started off with Gloria Contreras in classical dance, with very strict discipline. I was there for five years until I was bedridden by a horrible case of hepatitis, the doctor prescribing no exercise at all for a long while.

Though I had done drawings since I was a child, it wasn’t until shortly after I recovered that I began taking formal painting classes. Given its liberal reputation, the Academy of San Carlos did not figure into my parents' world view so they sent me to a Catholic professor, José Suárez Olvera. I became his assistant when he painted murals for the Church of San Francisco, but I left when I realized he was only copying the old masters. When I saw he didn't have a personal project I decided it was best for me to give up the apprenticeship. Then my parents picked the Ibero.

–But you had your eye on San Carlos.

–I was set on San Carlos because it was the art world, but I might have gone crazy there because of the outdated academicism that then prevailed. Looking around, and after asking myself the inevitable questions about what art is, it became clear that for me it was a language, a way of saying things, and so I had to find the best way of saying them.

–This language would become Grobet's incentive, her salvation–a religious concept that she associates with the creative act. In those days she first caught a glimpse of it at a private university in someone who became a key influence, allowing her to spread her wings: Mathias Goeritz, the driving force behind "anti-academicism"–a little-analyzed trend in the history of twentieth-century Mexican art. Grobet recalls:

–The courses for the Bachelor's Degree in Visual Art had already started. The first day I went to class I saw this wonderful man; I listened to his proposal and he asked us to bring some pieces of balsa wood to work on the following day. He was shocked when I came to the next class with my pieces of wood.

"Someone is finally listening to me!" he said, and kicked out all the students who hadn't brought their supplies. "What you've just done is break with the inertia that a woman falls prey to by not turning on the light when she's being serenaded."

–From then on Grobet kept close company with Mathias Goeritz. She attended his classes with her friend Silvia Gómez Tagle and followed his instructions to the letter. One day, with the most cutting, provoking tone they had ever heard, he asked them to bring back a "work of art." The young women brought an empty frame to class, and "an atomic bomb project" that delighted Goeritz. It was precisely the kind of irreverence that he wanted to talk about.

Thus Grobet understood the historical moment in which she was living; mass media offered new forms of expression and she began to question painting, printmaking, sculpture and the other techniques that were taught at the school. The only "modern" course was photography, with Katy Horna as the instructor. In the midst of all this, apathy was the student population's general response to both the academic program and the teachers. Goeritz gave up teaching and asked Grobet to be his assistant when he began work on stained-glass windows for Mexico City Cathedral. She accepted. Goeritz became her mentor and she adored him.

–Why did Goeritz have such a decisive influence on you?

–Because he was so irreverent and yet very contradictory and generous. He said contradiction is part of life, that it helps you grow. He told me that if I wanted to spend my life doing art I shouldn't take myself seriously, otherwise I'd be wasting my time. It's a shame that the priests decided to eliminate the program at the Ibero. Father Felipe Pardinas was someone who was open to new ideas, but the students were an apathetic bunch. We had good teachers: Guillermo Silva Santamaría, Miguel Anzures, Manuel Felguérez, José Luis Cuevas and Katy Horna, among others. Though I didn't have such an intense relationship with her, Katy Horna introduced me to the world of photography, which she considered more of a concept than a technique.

–But during all this you continued to do traditional paintings?

–Of course. I was looking for something in between abstraction, figuration and expressionism, and felt like a fish out of water. After the Ibero I took classes with Luis Filcer, a good teacher in spite of the fact that he interfered too much.. I later met someone who became a fundamental influence: Gilberto Aceves Navarro. In his workshop I learned to move with the brush and my body, to screw up, to throw stuff out and redo it, again and again. While I was experimenting with all this I still had my doubts and was struggling with painting because I still wasn't convinced it was the right medium. Then I went to Paris: that's when I decided to switch to photography.

–What were the reasons behind this crisis of yours?

–I was in Paris and felt something burning inside me. I didn't go to museums to see old stuff but rather visited galleries that showed new work. That's where I came across Kinetic Art: form, color and physics integrated as techniques into art and visual expression. Though the place was a wasteland on the national level, Kinetic Art is what inspired me to perform my first action in a jazz concert by Juan José Catalayud, creating an atmosphere for it with light and psychedelic projections that changed according to the music. Since then I've worked in multimedia, because I realized there was no reason for me to keep painting in the middle of the twentieth century. It was the time of mass media and that had to be the language I used.

–You then returned to Mexico and burned all your work.

–I literally grabbed drawings and paintings and made a pyre, I burned everything and locked myself up in my studio for several days. I acted on impulse and felt liberated by it afterwards. It was like saying: I got rid of everything–but seriously.

Art to me is like the act of living. And this made me think that devoting myself to it entirely would mean I might not fulfill other aspects of my life–like living with a partner and having children. So I pursued all of these things from the time when I was young, aware of the fact that my art practice would develop more slowly but more fully. I married Xavier Pérez Barba in 1962 and we had Alejandra, Xavier, Ximena and Juan Cristóbal. After giving birth to four children I felt firmly grounded; I was learning to be a mother, an important task that we never prepare for, trying to do the best I could while being aware of my limitations and mistakes. I was happily married to Xavier until personal growth and concerns of mine led us to split up.

One of these many concerns, which cropped up in 1971, was parachute jumping. It was something I'd wanted to do since I was a child though I thought I would never be able to. But since I always thought that you have to make your wishes come true, I parachute-jumped, and that led to a family conflict. But it allowed me to understand time, space and silence. The four or five minutes you are suspended in mid-air seem like an eternity; you feel freed, freed from time and in complete silence. This experience later helped me understand many things.

–And it also inspired you to want to become an astronaut...

–Yes, and I thought this wish would come true when I heard in 1985 that they were looking for a Mexican witness to go aboard the rocket that launched the Morelos Satellite.

I fulfilled all the prerequisites of the first phase, so I went on to the second. That's when it was going to be decided who the three finalists were.

Neri Vela's selection was obviously prearranged, but the three months I spent waiting and hoping were useful to me, allowing my imagination to take flight, since all my life I've always loved to fly–in every sense of the word.

–How did you get involved in photography?

–Photography was a solution to all my concerns: image, technique, mass reproduction and social relevance. I consider this last quality fundamental, because it's how you participate in the course of history. At one period in time painters were the visual documentary-makers. It's a role that photographers play in the present: writing history through images.

It was impossible to study photography back in those days–there was nowhere to do it. The only option was the Club Fotográfico, but I wasn't interested: they were still taking pictures of landscapes and the volcano. I told myself "I'll take the diy approach" and began studying, reading and experimenting.

By then, Jack Misrachi had just opened a gallery and asked me to do a show there. Looking at the space I decided to create a labyrinth with lights, mirrors and false floors through which gallery-goers walked. I worked with Silvia Gómez Tagle, and we made an installation though we weren't aware of it at the time.

I got divorced in 1974 and a year later I went to England with a conacyt grant. I wanted to go with my kids, but my husband wouldn’t let me. As a mother, I had to make a decision between being brave or being bullied. When I got to Europe I had great expectations about the experience of living in another culture, but I soon found out that schools are the same everywhere: they lay down rules that I wasn't prepared to follow. This made me get into fights with some teachers, but since I didn't have the pressure of getting good grades, I was free to do as I pleased.

–Did you ever lose heart? Did you have to leave the country to do what you wanted?

–I didn't lose heart because I knew what I wanted to do. I didn't have to go abroad either; I was doing what I wanted in Mexico and also in other places, but I've always felt that vital impulse to go places and meet new people. Besides, since the school in England was also closed-minded, my own perspective changed about the ugly, bigoted tendency to look at the so-called First World. I felt the same kind of rejection there that I had felt here.

–Your body of work is definitely congruent. Does it also have an element of provocation?

–It isn't my intention to provoke. It's more about a spirit of inquiry–though you never know its outcome. I've been through a lot, like the nuthouse episode in England, which made me think about who draws the line and decides whether or not you're crazy.

–What did you learn from your stay in England?

–It confirmed my suspicions that schools are good for nothing and helped me be more certain about the decisions I'd made, since I ended up doing what I wanted to. I felt very much at home there, and I don't know if that's because I felt compelled to contradict people who'd warned me that British people were hard to forge relationships with, or because it's part of my genetic makeup. I had loving friendships in all senses of the expression with really wonderful people, like Richard Sadler. My time in England helped me learn techniques in different visual languages in my creative work.

Before I left for England I began a relationship with Marcos Kurtycz, and while I was there we remained in love for two whole years by mailing each other. One project we had was for him to send me Mexican lottery cards he had drawn and written on and made into postcards. This piqued the interest of the mailmen in Cardiff, where I was living; they said how delighted they were about the mail, so I responded by sending photographs as postcards. All this established a dialogue between mailmen in both countries.

–You also had a working relationship with Kurtycz.

–I met him just after my divorce. I was looking for work, and went to the Fondo de Cultura Económica, where Marcos had a job as a designer. We met and sparks started flying. The most intense part of it all was sharing our madness. With Marcos everything was possible. What we did made sense and ended up being artwork. We shared the will to be creative in our everyday lives.

–Upon her return to Mexico, the time was ripe for Lourdes Grobet to find a conduit in which to channel her concerns about photography. The Consejo Mexicano de Fotografía was being created and she participated in its organization, as well as that of two Latin American Photography Colloquia. During the 1980s her work changed focus, centering on documentary photography and specifically on one topic that had fascinated her since childhood: Mexican wrestling or lucha libre. During this time she also worked at the unam's Science and Art Museum, where she met another artist who became another fundamental influence–Felipe Ehrenberg, with whom she would share her life and work.

–Life with Felipe, besides being fun, broadened the scope of our work, both as individuals and collaboratively. Circumstances in the 1980s made me switch from conceptualism to documentary photography. It was also a time when social causes needed as much support as they could get. I feel that during the time I lived with Ehrenberg I laid the foundations for much more mature work.

There were two important aspects to the collective work I did with Proceso Pentágono: that every member of the group had creative input and remained anonymous. Felipe left the group and my life in 1985. I continued collaborating on projects with some of the group's members until 1992.

1996

–How did the wrestling project begin?

–Like I said before, the members of my family were all sports fanatics and body worshipers. That pointed me towards wrestlers, whom I hadn't been allowed to see live because of gender issues. I had promised myself not to take photos of indigenous people or with a folkloric bent, but when I started taking pictures of the wrestlers I realized that they are like city Indians; I found that underbelly of Mexico I was so interested in.

Meeting the wrestlers gave me a new perspective. The one that most impressed me was El Santo. He's someone I also consider a teacher of mine. I was overjoyed to see how generous he was in his dealings with people. After seeing everyone else caught up in their own fame, I find out that the most famous man in Mexico doesn't give a damn about it and even plays with being anonymous.

–There is an anthropological element to your way of seeing.

–If I hadn't been a photographer I would've been an anthropologist because I'm a curious person and I'm interested in finding out about everything. For instance I've done work with theater, from my first collaborations with Juan José Catalayud and other bands, to my set designs for several plays starring actress Susana Alexander. All this came full circle when I found myself standing on stage for the play De mugir a mujer. Singer Margie Bermejo had asked seven women artists to consider what it's like to be a woman.

This experience–of going from being a spectator to an actor–was profound. I understood that on stage, your body, your being is your medium, your expressive weapon. Even wrestling is a kind of theater where the wrestlers are aware of their role as actors.

This experience–of going from being a spectator to an actor–was profound. I understood that on stage, your body, your being is your medium, your expressive weapon. Even wrestling is a kind of theater where the wrestlers are aware of their role as actors.

–The actors of the Laboratorio de teatro campesino e indigena (Campesino and Indigenous Theater Workshop) also interested you.

–When I suddenly saw myself doing portraits of indigenous people in the theater I chided myself for breaking my promise. Then I realized they weren't indigenous people but rather actors. I was dealing again with that underbelly of Mexico I am concerned about, but this time, transformed by art. The point was not whether they were Chol or Zapotec but rather that they were actors with tremendous potential.

María Alicia Martínez Medrano, the director, was my first Marcos. She introduced me to the indigenous world, the difference being that there, the world is transformed through art rather than guns. It's the kind of art I believe in: the kind that liberates and transforms. A sixteen-year-old told me that he wanted to be a guerrilla in Central America. "That's when I first came in contact with theater," he said, "and understood that you can carry out a revolution through aesthetics." These words, spoken by a supposedly "ignorant" campesino, had a profound impact on me. Though they might not continue to put on plays, communities are not the same after going through this kind of experience.

–You championed many causes, as was common in the 1970s and 80s: the Cuban Revolution, the Sandinistas and, ten years later, the Zapatistas in Chiapas. Nevertheless, one movement you did not get involved in was feminism.

–Besides being a great learning experience, De mugir a mujer opened my eyes about being a woman. We took the play to towns around Mexico and performed for women who had very diverse social and cultural outlooks; we held workshops and discussed gender issues. This kind of contact, added to my experience with the female wrestlers, broadened my concept of feminism. Instead of positing myself as a woman, I was always more interested in positing myself as an independent human being who doesn't bow down to anyone. I've never been much of a flag-waver and my attitude has been rather unorthodox, but I have fought for women's rights and equality. What I've always rejected is the kind of imported, middle-class feminism that doesn't correspond to the reality of Mexican women.

–You participated in the 1968 student movement and also criticized Castro while you were in Cuba. Your work often has a political element to it.

–My involvement in 1968 was inevitable. Though I wasn't a student I couldn't stay out of it. Since I was pregnant, I couldn't afford to be actively militant and expose my child, so I devoted myself to dissemination, communication and propaganda. My approach to militancy has been to use my work to help causes.

The Cuban thing was strange. I was invited to the 5th Biennial and its topic was emigration. I did a lot of interviews with and took anonymous photographs of all my revolutionary friends who had left the island. I interviewed boat-people, professionals and artists. My work was censured, and that was very painful for me since I was branded a traitor to the Revolution, when I have always struggled for it. In the press conference that the director held, I simply said that if such an important event could not serve to analyze the political situation in Cuba, then I didn't know where else it could be done. In the end the work was exhibited.

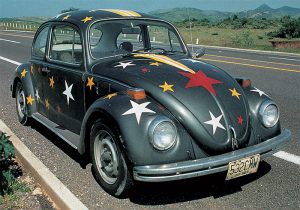

–You are anything but a conventional woman, and both your car–on which you painted a mermaid, and which was actually stolen–and your house–which is not your typical San Jerónimo mansion–reflect this fact.

–When I was at the Ibero, the Visual Arts program shared certain courses with the Architecture program, and this gave me a chance to accompany my classmates on visits to construction sites that were pioneering architectural projects at that historical moment in Mexico. That's when I found out about Manuel Larrosa's work. Years later I was able to buy a house he had designed for himself, and I enjoyed living in it very much; it is conceived as a sculptural space with a special attention to light, which changes according to the time of day and the seasons. When I met him, years afterwards, we ended up falling in love and having a passionate relationship since the house was like an experience we had shared. When we split up, it was like a cycle had also come to an end and that allowed me to leave the house.

–Having children was fundamental to your growth process, but so was becoming a grandmother. What is your experience of this?

–Becoming a grandmother gave me an enormous feeling of continuity. Unlike children who are your immediate roots, grandchildren give you a wonderful sense of long-lastingness.

–Besides making you feel very much alive, what was your experience of the twenty-five year retrospective of your work at the Centro de la Imagen?

–Thanks to Patricia Mendoza, who opened the Centro de la Imagen's doors to me, I was able to do a survey of my photographic work and situate it in time. The show was called La Filomena because in wrestling slang it's a move that literally means "mule kick."

I wrapped up another phase in my life with this show, like when I switched from painting to photography. It's when I felt the need for a transition from still photography to photo in motion–like video and cybernetic media.

–Lourdes Grobet–always irreverent, instigating projects and even setting certain people's teeth on edge–logically divides her life up into decades. She spent the 1960s creating a family; the 1970s represented movement, breaks with the past and change; the 1980s were characterized by emotional stability and growth and maturation on a professional level, while the 1990s were about conclusions.

The twenty-first century, the here and now, seems to be a time of liberation. Grobet left her house, closed her workshop and packed her bags to go traveling. She is going from Canada to the Bering Strait not knowing exactly what to expect, firm in her stance of not letting herself be overwhelmed by technicalities, though she will always insist on quality. And she goes off in search of other fateful encounters: landscapes in cyberspace or computer games that reveal our lack of consciousness about the planet–a village that is indeed increasingly global and virtual but also more uncivilized, as we have all had the ill fortune to witness.