Cubans outside Cuba - 1994

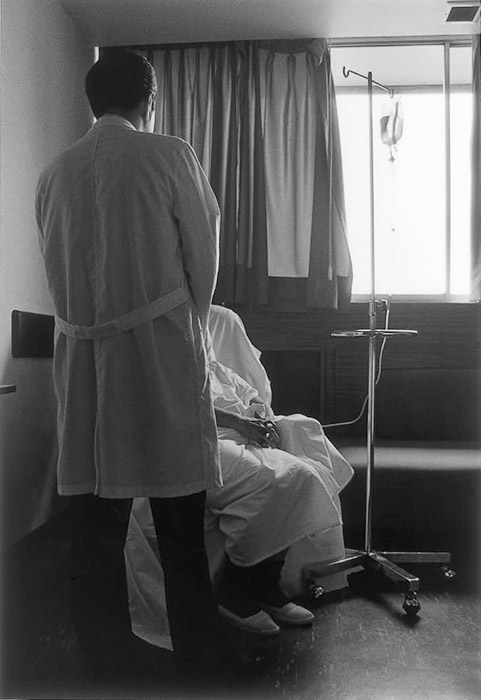

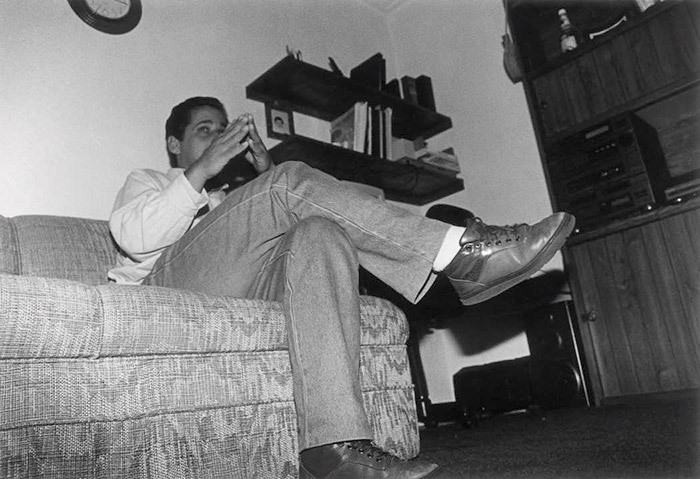

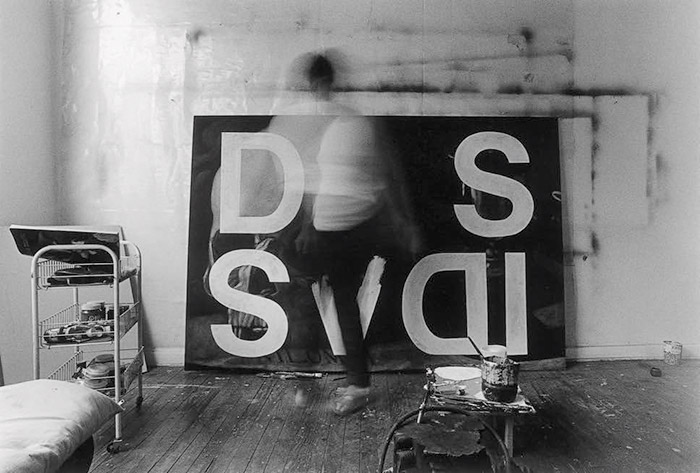

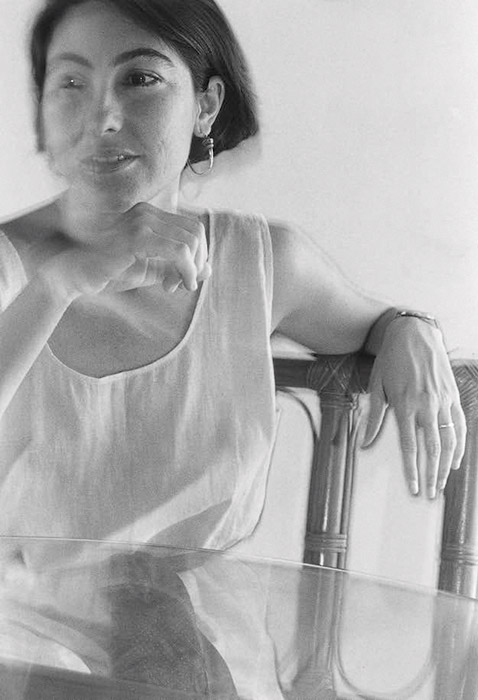

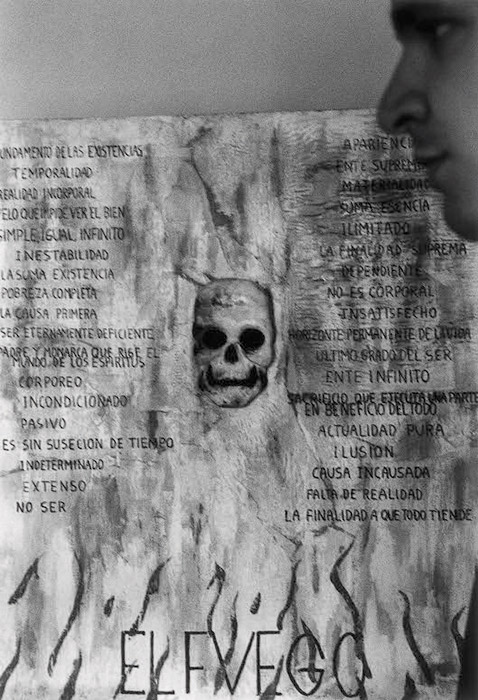

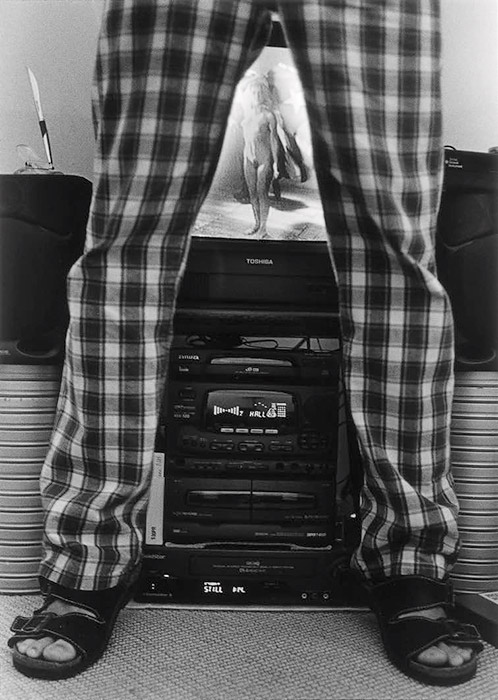

Photographic camera recorder, serigraphy printed texts.

Interviews to Cubans citizens outside Cuba.

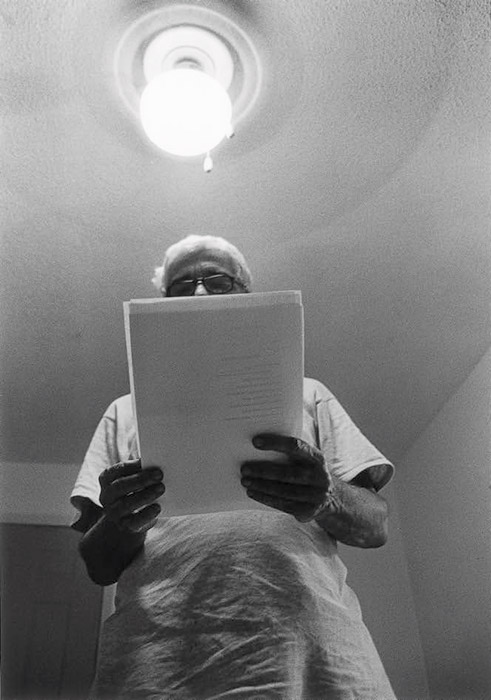

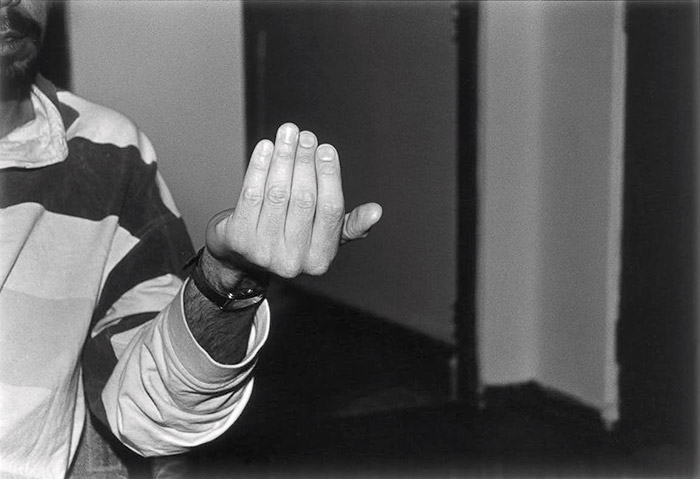

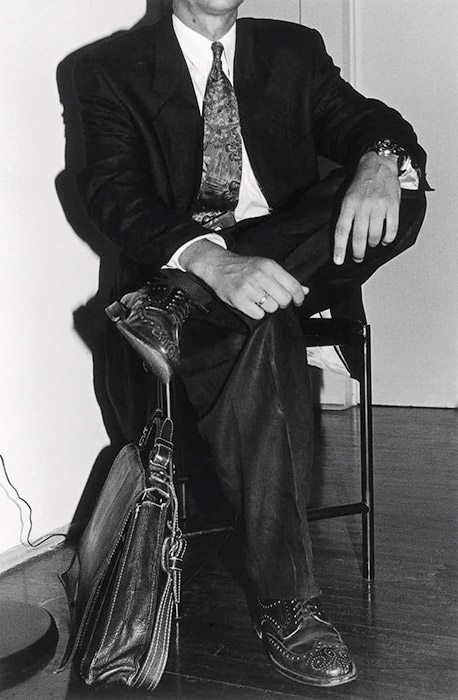

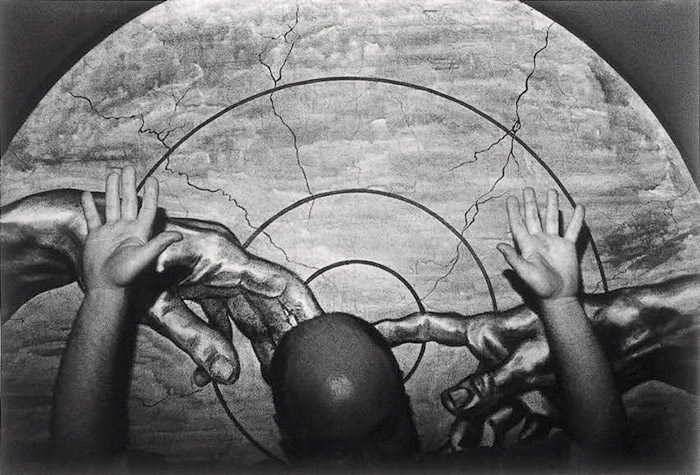

Unrecognizable portraits of people interviewed, accompanied by their respective testimonies.

La Havana Biennial. Havana, Cuba.

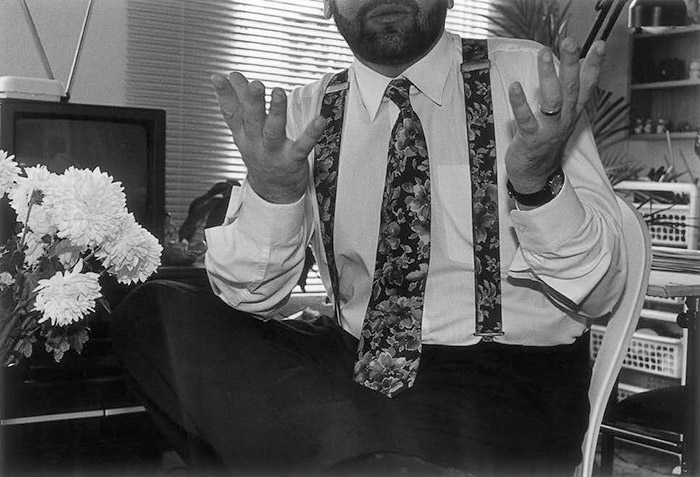

HISTORIAN

What happened to people from generation is that we went from a philosophical, historical reflection on Cuba's problems to a sort of critique of official cultural policies.

There arc two ways in which we could have an actual effect on the Cuban process: one is for official cultural institutions to give us some spac; the other is for alternative cultural organizations to reach a high enough level of development that they tan give us space.

There has been some change, though the Ministry or Culture has not acknowledged it publicly. Independent institutions have been allowed to continue operating or a mixed model has been followed, as in the case of the Pablo Milanés Foundation. These are all signs of disintegration rather than transition.

With my work I stress the need for change in Cuba. The starting point is not so much dissident organizations or political parties, but rather a greater openness to public opinion that allows ideas to circulate and that kindles the people's new political spirit. The revolution managed to politicize people so efficiently in such an unilateral and totalitarian way that it led to a sort of political illiteracy. In the article La otra moral de la teologia cubana (Cuban Theology's Other Moral) that was published in the Casa de las Américas magazine, I question the providential philosophy that the revolution applied to history, in which the official ideology claims that all of the events that took place in our country's history were leading up to January 1, 1959. Fidel has been built up as a messiah, and I try to demystify this construct, understanding history as an open structure, stripped of the notion of providence, with no set configuration or causation, looking for contradictions in the historical account of the Cuban revolution to salvage the past's plurality. The discourse of the 1960s was an idealization of the heroes of guerrilla warfare.

The nationalist mysticism of the 1950s disappeared when the revolution's socialist nature was declared and Cuba became a communist country. Leaders adopted different tendencies and discourses within communism and this created different factions within the government. What they did rule out was the possibility of a non-communist ideology. It's strange to see the way that many Catholics who gave shape to nationalist mysticism, like poets from the Orígenes group, were marginalized at that point and that some of them would reemerge as the organizers of the revolution's ideological discourse now that there's a crisis. The ideologists behind republican culture's Catholic mysticism are the same ones that are behind the return to revolutionary nationalism. When Fidel decided to ally himself with the Soviets, the first large scale cleanup operation began against members of this movement, who were inside the government though they weren’t communists.

My work discusses this new trend. Changes were traumatic. The July 26 Movement's brand of nationalism—the new main ideological tendency that was followed during the war in the Cuban highlands was not communist or anti-communist but rather social-democratic or of a liberal democratic bent. following in the tradition of Latin American populism. In the early 1960s non-comnitmist groups had been weeded out. Beginning in 1967 or 1968 the communist groups themselves were being weeded out, and the Popular Socialist Party's old members ousted as Guevarism was reaching its apogee; the whole political class was shaken up while it sought an alternative to the Soviet model which was introducing a discourse that would take root in the I980s.

There were irrational moments like the October crisis, when Fidel was fueling a global catastrophe. He would rather have had Cuba at the center of an international flare-up than see the Soviets humiliated by the United States. There are letters that Fidel wrote to Kruschev where he suggests that he launch the first missile—something he wanted to do, though neither Kennedy nor Kruschev did. This reveals a confrontational attitude that can amount to insanity. In the early 1970s another reordering took place, this time against the Guevarists, when Marxist-Leninism was imposed as the doctrine. The magazine Pensamiento crítico was closed down, the repressive movement against homosexuals began and old Guevarists were vilified. Fidel and certain figures such as Raúl and Carlos Rafael Rodríguez stood fast. A new group of leaders came to power who were pragmatic and spurned the use of discourse, the heirs of state institutions, with people like Roberto Robaina and Carlos Lage.

We intellectuals could have led to a change in Cuba but it was difficult. We were discredited for merely being abroad, but we kept working from here and discussing the issues. Those of us whose work is still published over there have a better chance of having a real effect, though ideas only circulate among independent groups, like Reina María Rodríguez's—independent institutions that aren't state-sponsored.

Another serious problem for Cuba has been US policy. We could have come to some sort of agreement with the US during the first months of the revolution. Batista fell from power because, among other reasons, they didn't lend him their support. Public opinion in the US supported the revolution—there was this sort of tacit approval that Fidel didn't manage to take advantage of. He immediately took a confrontational approach because of his grand anti-imperialist ideals and allied himself with the Soviet Union at the height Of the Cold War—when Cuba is only sixty miles away from the US.

Cuba has become a domestic political issue for the US because of the Cubans living there. The Cuban-American electorate wants Fidel Castro's government to disappear, so Washington's policies in terms of Florida hinge on this interest of theirs. Fidel aspires to reach in understanding with the America government while ignoring the issue of-exiled Cubans. He doesn’t want to come to an understanding whit his real enemies, who are the Cubans exiled from Cuba. There are two roads to take: reconciliation among Cubans–which would have the best effect on relations with the Cuban American Foundation and the Florida electorate and decide to deal with Castro. This alternative would be disastrous, because Cuban-Americans would boycott both governments.

I insist that the only way for there to be a change from within Cuba is for the state to listen to public opinion. The maiority of the people want a change with the government, not against the government. l came to Mexico in the summer or 1991 to study a Ph.D at the Colegio de México. I would only consider going back to Cuba if there were ample opportunities for me to get ahead in the intellectual or academic field.

FILMMAKER AND POET

I got into filmmaking by accident-I wanted to be a lawyer. I come from a family of fishermen, my parents were semi-illiterate. I spent my whole childhood with fishermen. I wore shoes for the first time when I was nine years old and learned to read at that age thanks to my father's help. In Santiago de Cuba, where I was born, there was a leprosy hospital that treated Haitians who had been brought as slaves to work on the sugarcane plantations. In 1945 it caused a scandal and the mayor ordered it be closed down. Then one day my father and uncle broke in around daybreak and stole whatever was worth anything. The iron beds were the most valuable thing. They took around eighty of them and my father dumped them into the sea. Later he retrieved them and took them to a Salesian college-the one that upper-middle-class kids in Santiago attended. He gave them half the beds in exchange for teaching me and my brother to read and sold them the other half. That's how I learned to read and I got a really good education. Many government leaders in power today went to school there.

During the revolution I was in the militia, a founder of the Rebel Army, one of Fidel's first men. The Cuban revolution was a necessary phenomenon, with its successes and failures, with its mistakes and advances.

When the revolutionary government came into power I had various options: to be a lawyer, a politician or an artist. The artist thing was fortuitous. When I was studying law at the University of Havana and the Film Institute was created, I was appointed administrator of a movie theater. The institute was staffed by well trained people who had studied in Europe but hadn't fought in the war. And I had fought in the war but didn't have a cultural background. But after watching them work for three months I decided to make a film. I wrote the script for my first short, a fictional art film six minutes long. I made it and everyone was surprised that an uncultured fisherman could make a film. That made them give me a grant to study in the Soviet Union and I spent five years there. In 1963 I wrote my first book of short stories and it got published. Then I started writing poetry. When l got back to Cuba I learned to make documentaries and continued writing–I’ve written the scripts to all of my films.

I'm a revolutionary, a militant, a mangy parrot. It doesn't matter what country I live in-I won't deny the fact that I'm an exile. I fight for the people's well-being and I'm a firm believer in Zapata, a firm believer in Rubén Darío, Proust, Mayakowsky, Walt Whitman; I'm not a political exile, I’m a traveler, a poet–that's my creed.

WRITER

I doubt the steps being taken are an honest solution. It's hard for me to believe that the course taken by Cuban politics in the 1970s and 80s actually made the Cuban people its priority—it was more of a lust for power. I also doubt the people would become the priority even if there were to be a shift to state capitalism.

My generation, now in our thirties, suffered less than the others because we believed in the revolution. It was the era of Soviet influence, when we believed in changing the country through technology, and that gave us energy.

Most of the tensions existing in Cuba stem from personal expectations created by the revolution in terms of intellectual development, or from the repression exerted in very concrete and subtle fields such as literature and theater.

ARTISTS REPRESENTATIVE AND PHILOLOGIST

I graduated from the tiniversitv of Havana in philology, but this field didn't really suit my character and little by little l started working with I artists. This allower me to better organize my time and I was able to study art history. I've devoted myself to promoting artists and live shows in both Cuba and Mexico. Over there I worked more independently, without institutional support, but here I have a company backing me up. I was privileged in Cuba because there weren't that many good promoters who also enjoyed what they did. I never worked with official cultural institutions. Not because I didn't want to, but because they never asked me, and now I’m glad they didn't because people who did work for them carry a heavy burden for putting their personal interests before work: they would book artists, even under unprofitable conditions, just so they could travel. It was hard to work freelance because most people preferred to contact the Ministry of Culture directly. I've always thought that artists shouldn't be promoted by artists but rather by promoters who have a real sensibility and knowledge of culture.You can't handle them like politicians because that simply doesn't work.

I came to Mexico to teach some seminars at the Canal Once television station in 1992 and I wasn't thinking about staying. I presented several projects with the groups I handled, but I came up against a situation that made it very difficult to promote Cuban artists. Here I realized that capitalism was quite different from what I had been told. Both systems are a complete mess.You’d have to combine them to create something new and better. I'm very glad to have experienced both situations. It's not only the promotion of a cultural project but also the motivations behind it that are very different in each system—from the initial conception and development all the way to the show's actual staging.

I had a very happy childhood. I come from a humble family; my mother was illiterate and a housewife, and my father did bodywork on cars, but my five brothers and sisters and I were able to go to university. You can say a lot of bad things about Cuba, but you don't have opportunities like we did to get an education in other countries. I was able to study what I wanted to. We didn't only have access to schooling and the academic infrastructure, but also plenty of opportunities to go see plays and films, without having to worry about having enough money to buy a ticket. You could see movies from all over the world and not just Yankee films like you do here.

In Mexico it’s horrifying to turn on the TV and see the monstropoly that is Televisa. Over there the soap operas at lost have a historical component, they're very low-budget but they have content. Here it’s like a monster imposing its own tastes. Things are changing in Cuba though.You can't give people that level of education, who at least completed ninth grade and are thinking individuals, very aware of their disgraceful situation... For someone who went to school, it's very frustrating to see that your life will never change or progress and that you don't have opportunities for professional development and even less for getting your work out there or sharing experiences with people from other countries.

Socialism is a very complex system. It's great in theory, but putting it into practice is another thing. It's an ideology that seems superior to me in qualitative terms but it doesn't work. Our system has made Cubans anti-imperialists. Most people want change, but not with the Americans; they want an inner, gradual, progressive change, without the hegemony of someone whose fifteen minutes are already up and who has become a dictator.

SALES EXECUTIVE

I believed in Fidel and in the revolution until I was eighteen. When I started university, realized that some things just didn't work.

There has been an insidious repression: you have a career only if you fulfil your obligations as a militant. It's frustrating not to find work when you get out of school—only members of groups supporting Fidel get jobs. You are given a good education, you are prepared, you feel ready to take on the world, and you can't do a thing about it... You always want more—development is an ascending spiral.

I'm making a future for myself here. In Cuba I felt like I was dying. I couldn't do anything; I felt like I was wasting time, without aspirations, without hope.

My father was a revolutionary, the only member of his family to stay in Cuba. He raised us with those ideas. When I had the chance, I sent him to the United States to see relatives he hadn't seen since 1978. He returned a changed man—he felt like he had given tip his life for nothing.

I think that if all the Cubans who have emigrated to other countries had stayed, something would have happened by now.

PAINTER

I was born in 1963, with the revolution, and no one asked if I wanted to be a Marxist, a Catholic or what.

My father was a revolutionary, a naïve but firm supporter of Fidel. That was how I was brought up. When I enrolled in the Higher Institute of Art I came into contact with the children of the leaders, and became aware of the huge class distinctions that existed. The different social strata were in clear evidence.

Besides all the other bullshit it broadcasts, Radio Martí did play an important role in getting people to realize what was going on. It began to denounce the leaders' properties and some of that information was eventually proven true.

I wonder what we've achieved. There was a revolution so that everyone might live a better life, and nothing has happened.

DOCTOR

I was a doctor at a renowned hospital in Havana when I was notified that State Security was looking for me due to political and moral problems. It took me almost two years to leave Cuba. I finally managed it in 1989.

I was raised in the bosom of a revolutionary family, very conservative, that was very close to possessing power. I studied with the children of revolutionaries, in a school for the privileged classes. We would spend summers on these yachts that the leaders had in Varadero, we ate at the best restaurants in Havana, we'd go on outings to these huge estates in Santiago, and we thought everyone lived that way. We thought we lived in a country where everyone was equal, where we all had the same opportunities, until I realized that I was a rich kid who never left Miramar.

It was only when I studied political economics at the university that I began to understand the capital cycle, the source of wealth. I was overcome with self-doubt, and felt like a parasite on society. The other experience that made me understand my situation was going for practical training at a polyclinic in Old Havana, which had only ever heard of Varadero.

WRITER

One of Cuba's tragedies is that so many of its intellectuals live outside the country. We're working on the idea of forming a group of Cuban intellectuals living in Mexico and other countries, to create an information center that will act as a repository for all the work Cubans are producing off the island. There is some interest in reviving the traditions that were lost following the revolution and its process of institutionalization of culture, which resulted in a monolithic expression divested of the customs and peculiarities of different ethnic groups.

A writer can produce wherever he or she may be and under any circumstances, but I believe that exile broadens one's horizons. The writers in my literary group are called Novísimos (meaning the latest, or brand new). We were born with the revolution and our subject matter focuses on disenchantment, despair, frustration... We don't know how much the revolution achieved or if its even over. We believe that we have a body of work to preserve, notwithstanding any political principles. The meaning of an artist's life is his or her work, and at the moment, it is impossible to develop it in Cuba, for both political and economic problems.

Cubans possess the seed of utopia. We are not resigned to the sudden downfall of what we believe in. We all have hopes for a better world, but what with all the Cuban system left us, it is hard to believe in it.

Cuba was the rationale for installing military regimens throughout Latin America. If the Cuban political system doesn't work, well, neither does the Mexican—that's an attitude I don't like. We all have to contribute something to the world to change it, so it will generate something new, or combine tendencies to improve the situation. It is very difficult to let go of an illusion.

Cuba has not had the same degree of corruption as other countries, but the laws have made the leaders virtually untouchable. They may not have dollars, but they certainly have power.

There used to be poverty in Cuba, but there was also dignity. Today. there is moral and spiritual bankruptcy, a feeling- of frustration for having been exploited for the sake of life, of history... People just want to acquire dollars to be able to leave. The measure of all this is prostitution.

PAINTER

As a painter in Cuba, you felt a little more at ease, with fewer pressures. You didn't have to worry about appealing to a large market, which gave you some peace of mind. You didn't satisfy pressing needs, but neither did you create them. Cubans don't have pressing needs: after so many years of stoicism and sacrifice, we are able to live with just the basics.

We lack focus. I say to myself, "I have lost my focus; I have to change the way I live my life."

Everyone hopes this will pass, that the situation is temporary, but when I wonder about going back, I think that I have emerged from the womb and I do not want to return.

PHOTOGRAPHER

I was taught to think and now they don't let me. Cuba has been subjected to a control mechanism. And not just control—limitations. They limited thought. Those limitations created distrust, they made people lose heart, and logical or dialectical movements began to emerge, because one thing leads to the other. They nipped that movement in the bud; they put an end to a mode of thought that really did exist.

Everything needs renewal. What was once considered revolutionary or advanced thinking is no longer revolutionary ten years later.

My parents' entire generation, people now over fifty, was very revolutionary. They were the awakening of an international movement that is not as strong as it once was. It began to stagnate because there was no dialectical development. They themselves misinterpreted Marxism, making of it whatever they wanted to.

In the late 1960s, there was a strong student movement in Cuba that emphasized critical thinking. Those people—all of them philosophers—promoted independent thought that corresponded to our own reality and not to Soviet, German, or any other imported thought. It was a philosophy that would uphold a new way of life. It wasn't permitted—they eliminated it.

ILLEGAL EMIGRANTS

We have been persecuted by the police for having formed the Cuban Party for Human Rights, of the National Cuban-American Foundation. Our party carries on a pacifist struggle for the restoration of human rights. Our activities include assisting political prisoners and their families. There are a lot of opposition parties. Ours is national and clandestine. Many of us had no intention of leaving Cuba but had to because our lives were in danger. We left on February 24, 1995 and reached Contoy in three days.

This is the first time I have left Cuba in my thirty-nine years of life. It’ the first time I've been on an airplane and I've seen things I had never imagined. I’ve eaten foods I had never tried before, like apples and meat... We are awestruck by what we see—things that are normal here. We feel odd; it's a strange situation. Our lives have changed completely. Even what we dream is different.

Our Party organized the trip. It was all done in secret. Even the candidates for the trip were informed just minutes before leaving, for fear of being reported. Leaving our families was very painful, but we can only help them from outside. We can't risk our children's lives. If we are killed, nothing is lost, but if innocents die, all is lost, because they haven't had the chance to live their lives.

One of the reasons I was fired was for belonging to the Catholic Church. The State Department suspended me for participating in outside activities. The charge: inappropriate political and social conduct, because it didn't conform to the revolutionary process.

I preferred death at sea to dying on land. At sea I would have died a free man, and on land I would have been beaten to death or shot… I am here, full of thoughts and ideals, but I am not free of emotions, because a man who abandons his homeland and his family can never be free.

DESIGNER

Things in Cuba are confusing.You think the country is going under and a few months later it is resurrected like a phoenix. The economy that was practically moribund may have had a resurgence, but it's awful to see how everything that was once prohibited is now permitted. Before they wouldn't let just anyone join the Party, but now they accept religious people, homosexuals, dissenters. It's obvious they're running out of supporters.

I am very fearful of the drastic changes in Cuba. The experience in other socialist countries has demonstrated that Cuba is not dialectically prepared to switch over to a capitalist society.

PAINTER

I arrived in Mexico in 1991. It was a period of transition for me to the United States because the legal status you are given in Mexico is far from appealing. In Mexico I felt like I was still depending on Cuba, while in the US the policy is to grant you citizenship right away–it’s the ideal country for Cuban inmigrants. I’m getting citizenship out of convenience and for practical reasons, but I will always remain Cuban, I’m not worried about that.

There’s no place for us in Mexico–it's a country with a very staunch culture, almost impenetrable… or rather it assimilates you, makes you part of it. I worked at the Universidad de Monterrey and had time to think there–I understood a lot of things about Mexican culture I had observed but not understood. I saw the real Mexico–the countryside and places where the civilization that calls itself North American has not yet become dominant... I also got to see the work of many artists. Mexico has a capitalist system, but it's a gentler kind, you have more time to think there. I haven't seen the same corruption here that I saw there, but in terms of violence it's similar. The United States is a racist culture but it isn't xenophobic–there are now several Cubans in public office.

I had a good life in Cuba. Since I was an official artist I was privileged. I had a career but I didn't like the idea of doing everything they asked me to do like a sheep. That’s why I decided to leave. The US is a good place to prove yourself. Those who have managed to become famous artists in Mexico have then had to try and make it there. Another appealing thing about the US is money–it's the basis of everything. In Cuba I was paid with good materials, things I can't buy here, but it came with control and manipulation. I have to say they didn't impose a style on us, we were very privileged then. Censorship came when the exodus started, around 1987. Between then and 1989 a lot of heads rolled.

I don't live of my painting. I work doing other things like many other artists. Here I earn money in museums: moving paintings, hanging shows, painting walls.

There are major differences between different groups of exiles, though I fed like now we're becoming more united, Cubans in Miami think that when Fidel's regime falls, they will be the rich Cubans and the ones over there will be the poor. That the investments of people from here will make the economy grow.

I feel sorry about what's going on in Cuba. Intellectuals and culture are in a terrible state of crisis–the exodus is leaving behind people who are all alone, the country is becoming impoverished.

WRITER

I studied in Moscow for nearly two years. I came to Mexico in 1991 and stayed. I write essays and literary criticism, and I translate, poetry in particular. In Cuba I was part of the group Paideia, along with other writers and artists. It was a project to reform the cultural policy of the revolution. The most important artists of the 1980s took part in that group, and later had to emigrate.

Paideia made an appeal to intellectuals, by means of a fairly controversial document, to come out against official policy, resulting in the usual consequences of censorship, alienation, harassment. For two years, we could not publish anywhere, and even in intellectual circles we were considered overly politicized.

But I wasn't interested in making a career out of dissidence. That's why I came to Mexico, where I taught at several universities and began publishing in diverse media. Today I work as an editor and have a more or less constant association with Vuelta magazine and the group of intellectuals who publish there.

Politically, I consider myself quite conservative, "right-wing" if that expression has any meaning these days. I think liberalism is the most civilized system of convenience we can find, but it hasn't been able to shake off the illusion of equality.

I think that in Cuba we are witnessing the decline of one culture and the advent of another, equally decadent one: the intellectual élites alienated by political and academic commitment, ideology versus style and the multicultural revisionism of the Creole canon. Our Cubanologues are so busy deciphering the origin of Evil that they have forgotten that the Great Plan of any dictator, Fidel Castro included, is to invalidate the Landscape in order to impose History, substituting the idyll of culture for the idyll of politics.

To me, Mexico is a more interesting country, with a vibrant culture still living under many specters and shadows: a kind of historic Walpurgis. This lends it a particular interest to someone who doesn't believe in culture or in society.

I’m afraid that recent reforms will allow for a market to be created in Cuba without creating a system of liberal opinion, without social liberty and without redistributing the public sphere, but rather with a state that controls currency and can control the economic market.

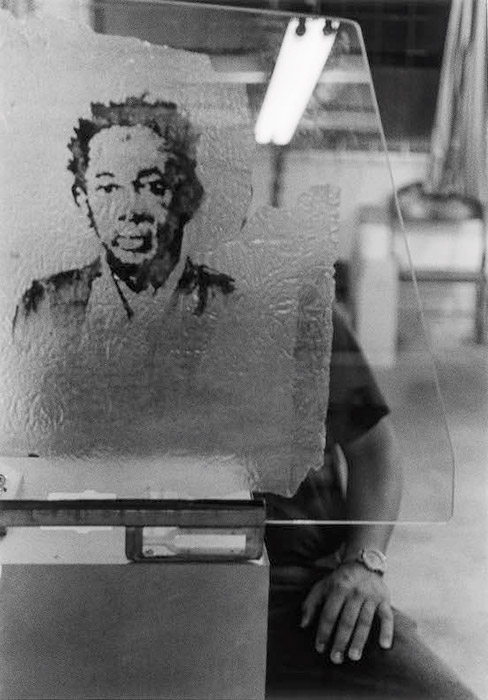

PHOTOGRAPHER AND PAINTER

I came to Mexico in 1991 and stayed a year and three months. It was impossible for me to get working papers, so I took advantage of an invitation to exhibit in the United States–I decided to stay in Miami and shortly afterwards found a gallery that wanted to represent me. At first it seemed like a rather strange place but it slowly won me over–I knew that I would once again feel like I was in Cuba.

This is nation of immigrants and in Miami most of them are Cuban, something that helps when you're starting all over again... you have a lot of friends. Immigrant groups or factions have very marked differences. The first to leave Cuba did so for political issues. They were wealthy people who had had everything taken away from them. I'm talking about industrialists, landowners, doctors, merchants, businesspeople… there were no intellectuals or artists because most of them had lent their support to the revolution.The few dissenters there were early on went to Europe. At that time Miami was a small town. The city and the economy grew with all those people, but there was no cultural scene.

The second large wave of immigration was from Camarioca, made up of people who went looking for their relatives who had settled in Miami earlier. This had led to a domestic problem in Cuba because people who kept in touch and corresponded with their relatives were denied jobs, the right to study, they were forced to totally break off contact with them. There weren't very many intellectuals in that group either.

Then Mariel came in 1980. That was a shocking trick because it was a pretext for emptying out mental hospitals and prisons, something that turned Miami in a dangerous place for muggings, murders and rapes. That time a small but significant group of intellectuals, painters and professionals left and started again from scratch. In contrast to all of these, in the group that came through Guantánamo there were all sorts of immigrants, but essentially professional artists and intellectuals.

Lastly, in the Cuban-American group–people who were born here–there are very worthy individuals, intellectuals who are brilliant but don't sympathize with the intellectual movement in Cuba. Those are the people who buy the art we do.

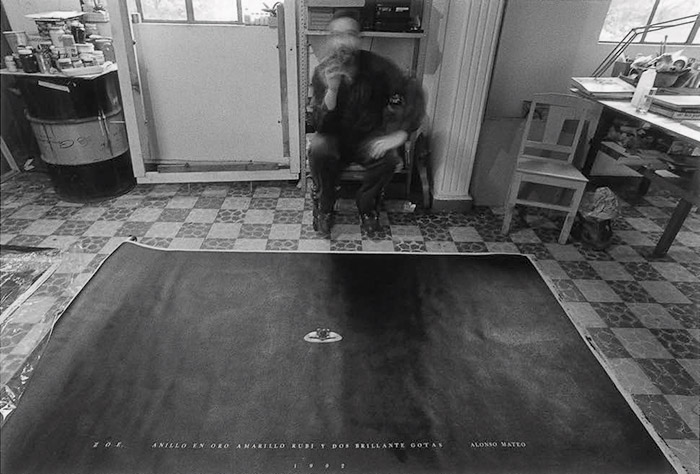

PAINTER

The premise of my work arises from frivolity. I paint the world of values like a return to the aristocracy I see coming back, for better or for worse, and perhaps as a backlash against socialism... like a return to money, a return to aristocratic capitalism, not the typical capitalism we all know.

I believe in money and in property, I need them. For that reason I want my paintings to be investments rather than works of art. I consider the future of art to be a problem for science fiction to sort out.

ARCHITECT

I left Cuba in 1990 for Budapest, during the breakup of the communist bloc, I was there for almost two years and in 1992 came to Miami. I worked in a city-government office tor five years doing historical building restoration, urban recovery projects and special city-planning projects.

When the revolution took place there was a tremendous moment of creativity. You could do anything, everything was changing, and in that moment of chaos there were possibilities for expression. With time the system became institutionalized and degenerated into a dictatorship.

In the 196s in Cuba there was a great controversy between the humanist bent in architecture and the technological, scientific one. We humanists ended up losing that battle. Many of them even had to go into exile, since their brand of architecture didn't represent the system's interests. It was considered idealistic, kind of crazy and a cult to individualism. The wonderful art faculty buildings in Havana are an example of it.

My generation sought to escape the strict rules of professional practice to express ourselves more freely. Fed up with the expressive vocabulary then being used in the field, we started associating with visual arts, doing projects about utopia and reality, doing interdisciplinary activities, playing. This made us feel better than standing around supervising boring construction sites.

Residential housing projects, especially in the eastern section of Havana, had been conceived under the Batista regime and started getting built when Fidel came to power. They are the product of continuity rather than of the revolution. The Plaza de la Revolución had been planned since 1905 and the project was to locate the National Capitol building there—the seat of government. In 1953, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of José Martí’s birth, the Batista government built a modernist-style housing project that Fidel turned into the stage of his speeches and military parades. He wanted to transform the place into something like the Kremlin that was representative of his power.

In socialist architecture they made you use codes and designs imported from the Soviet Union. One example is the system that the Soviets sent in the 1960s to rebuild Santiago after a hurricane. It was old, obsolete and it had nothing to do with the kind of weather you get in Cuba.

Here to Miami I've come up against .all the obstacles you face as an immigrant, Nonetheless I’ve started teaching, something I was never able to do in Cuba because my way of thinking didn't agree with the school's.

PAINTER

I admit the Cuban health program has been quite good, as well as being free. But things are very bad now. People have access to hospitals but medicine is scarce. It has always been the custom among Cubans to seek relief from healers and santeros (witch doctors), and though this was never entirely forbidden, it led to subtle repression, such as being passed over for promotions at work, or your children being submitted to pressure at school. Now santería is stronger and much more open, to the point of it being used as a tourist attraction.

As a country, Cuba has always been subsidized. It has never produced anything. Agricultural policy has been a disaster. The environment has been damaged not by industry but by the army, who have destroyed huge networks of grottoes and caverns in the construction of underground military bases.

I think that now, there is a new capitalist system coming into force on the island—one which excludes Cubans.

HOMEMAKER AND POET

In Miami I've gone through all sorts of states of mind but in general I feel good.

I firmly believe in the importance of family. People who have managed to get their families out of Cuba and have been reunited are out of harm's reach.

With the revolution there was a marked tendency to break up families. Military service, busy mothers, their kids being indoctrinated in the countryside were conditions that kept families separated for long periods of time. Political attitudes were another factor in breakups as disagreements caused rifts between family members.

My family fell apart when some of them started leaving the country. You got into trouble for just staying in touch with them—it was reason enough for them to keep an eye on you and for you to have problems at work or at school.

When a family member got married they had to live with the rest of the family because they had no other place to go—in overcrowded apartments, leading to problems like promiscuity, because houses were divided up into tiny little spaces. All this made it difficult for people to become independent.

My son was one of the main reasons why I considered leaving Cuba. I wasn't convinced about the course the system had taken and I knew that if I told my son about my own convictions he would have trouble adjusting to getting a different kind of ideological guidance at school. Just thinking about my son having to go to Angola at the age of sixteen terrified me.

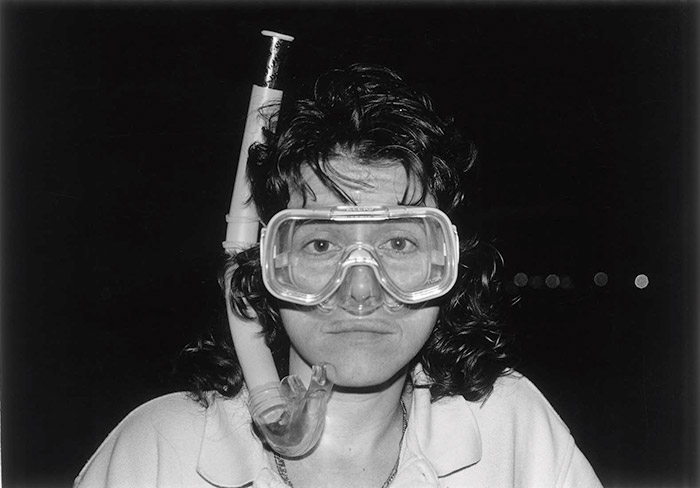

DIVER AND ILLEGAL IMMIGRANT

I've always liked everything that has to do with the sea. I wanted to study marine biology, oceanography, but it was really difficult—not for the grades you needed but for how socially integrated you had to be. If you have relatives living outside Culla and you stay in touch with them, you're marked. It doesn't matter if you have good grades, you're denied access to school. Plus I never agreed with die government and that got me into trouble from when I was quite young. The two reasons why I couldn't study what I wanted to were because my family were dissidents and because I was a woman.

My rebelliousness since childhood is what made me leave Cuba. I made three attempts on rafts before the boat-people crisis happened. The first time we had to turn back because the sea was too choppy; there were three of us—two girls and a guy. On the second attempt I was with two guys. That time we ran into the coastguard and jumped into the water not to get caught. We swam five or six hours, practically all night long, until we reached the shore, covered in cuts and scratches from the rocks. The third time was in Varadero. Two friends of mine and I got a proper raft and we left with food and water. A fisherman saw us and notified the authorities. We were all taken to jail and weren't allowed to contact anybody for five days. They tortured my friends to get a confession and I had to admit we were trying to escape.

Several months later I met a Spanish man—we fell in love, got married and went to Barcelona. Things went very well for me in Spain and I joined a diving club. Over there the ocean is nothing like around Cuba but I was doing what I enjoyed. After being there for three years I felt like seeing my family again. I had a goal that's very typical of Cubans: getting to the United States. What you want the most is what's taboo—everything American was "evil" in Cuba, so it's what you're drawn to... forbidden fruit is always the tastiest, the most exciting.

I went to Madrid to ask for a visa for the US and they turned me down. I had to wait six months before I could apply for it again, and because of my political past they turned me down again. I went to Mexico, contemplating the possibility of entering through the northern border. I got my papers and asked for a US visa as a Mexican and didn't get it. So I got on a plane and went there like what you call "aerial boat-people" who get a ticket, don't get asked for their passports and when they land, no one dares to arrest them because their rights are protected by the law. They're offered political asylum, they're put on a kind of reservation for two or three days in the airport and after an investigation, they're kept in detention for a month and a half. When I did it, there were around 300 or 400 Cubans waiting to get their work permits. Once you've gotten it, they let you out.

Though I'm close to my family I don't like Miami because everything about it is so materialistic. It's not what I expected, it makes me very nervous, I have no control over my reactions. I haven't done any diving. Being so close to the ocean and not going in the water, not being able to focus on that means something's wrong. I can't relax enough, be calm enough to be able to dive, because it's not just about jumping into the water—you need peace of mind and composure to do it. Here you work more than live your life and I'm more interested in living my life than working.

PAINTER

My experience in Moscow was hard. When I went there I had great expectations about getting to the cradle of socialism and all I found were protest demonstrations, rallies and strikes. We knew nothing about this in Cuba—the press censored everything about the breakdown in Eastern bloc countries. I was also surprised to see that art was very official and that there was a lag in terms of information.

In Cuba-there were cultural policies that tried to impose socialist realism, but it never fit into our scheme of things and it never thrived. Cubans are not that schematic, insensitive or closed-minded. Besides, we are as close to Pop as we are to other avant-garde American movements.

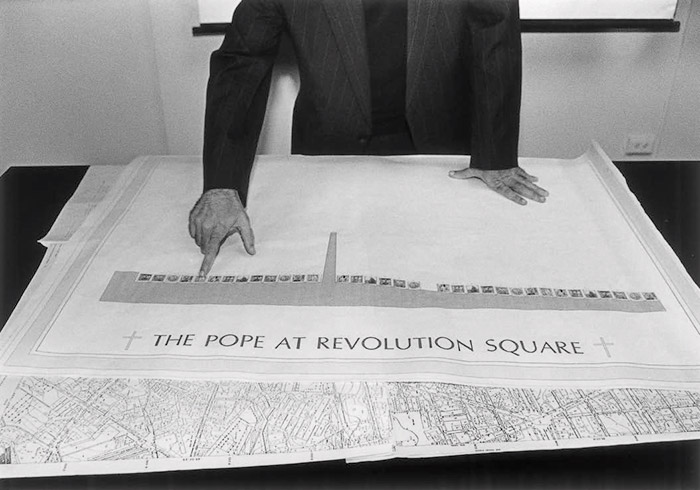

FILM DIRECTOR

The problem of Cuban exiles or emigration has to be viewed from when Cuba began to gain a sense of itself as a nation, in the nineteenth century. A beautiful Cuban legend mentioned by a theoretician of my generation, Iván de La Nuez, dates back to that time. it refers to Matías Pérez, one of the first people to fly in a balloon, floating tip into the sky never to return. De la Nuez has advanced the very poetic notion that this was the first attempt to transcend the Cuban nation's insularity.

The conflict telt by any islander–whether Irish, Cuban, Japanese, English or from the Canary Islands—is that of transcending what Virgilio Piñeira called "the damned circumstance of this island surrounded by water on all sides.” Accordingly, Cuban exiles not only have economic or political motives, but an anthropological essence deriving from the islander’s condition that is conducive to a sense of insecurity, instability, inequality and being cut off from the world.

An individual from an island always tends toward tectonic security. This is a kind of egocentrism that exists in more of an anthropological sense than a cultural one. It does not mean turning to New York or Paris out of an intellectual or cultural urge, nor for the urban clamor, but to escape a place of captivity, because there is no escape from an island. Rather than resolve the Cuban's conflict over insularity, the revolution only aggravated it. It was like fencing of the sea. That is why we have that hunger, that longing, that need to leave. On the other hand, despite its apparent insignificance as a nation, a country and a geography. Cuba is an island that has always felt the need for belonging and integration in the world. There have always been important people there. The idea that they owe their existence to the revolution is a lie.

Castro's rule has been characterized as a dictatorship with poiesis. It is a subtle dictatorship. with a good command of language, not the crude, brutal dictatorship of a Pinochet. Fidel is skilled at managing his personality, his process, his work—which is in fact a collective achievement that he appropriated, as he only can lay claim to a small part of what was achieved by thousands and thousands of young people, intellectuals, guerrilla fighters. university students, street people. The revolution was a democratic process, not the magic of a single man.

The essence of the problem of Cuban education is whether it is indeed free or not, and whether it started with the literacy campaign of 1961. The objective was to give the entire population a certain basic level of schooling and academic instruction, which did not mean that the masses became cultured nor that they acquired an elevated spirituality. School was free, but in quotation marks, because as Marti said, "capitalism is man's exploitation of man, but socialism is the State's exploitation of man.” And the Cuban revolutionary state exploited its people and continues to do so. Yes, we received an education, but I do not owe my education to Fidel Castro: I owe it to Manuel Moreno Fraginals, my professor of urban culture, or to Gustavo Pita, a philosopher educated at Russian universities, and to many other teachers who loaned us books to photocopy, because in Cuba, we do not publish authors considered to be enemies. A country that does not accept contradiction and difference will never develop.

The revolution created an Art Institute with litany limitations. I studied at a filmmaking school without a single camera, or editing room, or cassette, or anythin. The San Antonio de los Baños school has been a school for foreigners, designed to offer a certain image to the world, as only three Cubans were admitted each year. I was able to take some workshops there thanks to my friendship with Fernando Birri, otherwise, I never would have been admitted. Castro created the school immediately after the apparition of the Miami television network called Tele Martí, which had plans to broadcast into Cuba. As there was nothing he could do about it, he said, let's train some people who can respond to this." Of course, telecommunications resolved that conflict by diverting the signal, so we were no longer necessary.

In his essay "Ideology and Revolution," Jean Paul Sartre explains that the Cuban revolution has no ideology—meaning an idea that distinguishes the praxis or emerges from the praxis—but an idea that he referred to as the ideology of rebound. Recall the famous Havana Strip. Fidel decided to raze all the fruit groves and cultivate coffee—quite an unscientific move, but it had gotten into that lunatic's head that be was also an agricultural engineer and he wiped out all the fruit trees in a fruit-producing country. Then he decided to switch to sugar cane in 1970, which was another failure. And that's how it went with a number of different crops, and nothing worked. This is an economic ideology that is constantly being improvised, patching up flaws, finding new ones, responding to the viewpoint that always places us as the enemy outside. Because Cuba has always defined itself in terms of the enemy outside and not the enemy within. We haven't wanted to acknowledge the enemy's presence there, nor the fact that he has sold himself to us as the nation's redeemer. Because in Cuba people are as hungry today as they were prior to 1959. There is a lot of disease and the people are dying like flies.

A curious fact: nowhere in any of Fidel’s speeches or texts will you find an allusion or an appeal to love. In Castro’s history, you won't find him addressing lovers, or referring to love, like you do in Martí’s history. The strongest emotion Marti had was compassion. He was a man capable of forgiving his own murderers. But contradict Fidel Castro or disagree with him and he has you shot. There are thousands of Cubans living on or off the island who have lost a family member that way.

How else can you explain that all the great movements of the 1960s–hippies feminists, the Beatles, gay liberation, national liberation...—were banned in Cuba? The revolution monopolized everybody's attention and expectations, but the country started to fall behind the rest of the world. All the prototypes of the 60s were prohibited. The artistic avant-garde, the very basis of postmodernism, the high point of the great utopias—all were barred entry. The political leaders had everyone in their pockets. You would watch those beautiful men with full beards, redeemers, liberators, giving all power to the people, but it was all just an euphemism. Everyone knows that, because true power lay only in the hands of an elite of politicians and military men. Something else Fidel Castro did was abolish the freedom of belief and impose atheism as the general religious ideology.

How many women have you seen in the upper ranks of power in Cuba? In a nation of machos, women only govern in the home. They are responsible for keeping the family going, for not letting it fall apart, something that Fidel will not admit because he has never had a family

There is an essay on the Cuban family that demonstrates the effects of the revolution. The wars in Angola, Ethiopia, Vietnam and Nicaragua kept people away from their homes for years. What relationship can be salvaged under those circumstances? That spells the end for the family. Contingents of cane harvesters, sugar producers and construction workers would spend months without ever seeing their families. Another factor in the destruction of the family were the field schools. For instance, starting in junior high, I would spend weekdays in the country, and for five years—at the most important age in a person's life—I would only see my parents on weekends. Why? Because we were an unpaid labor force. We were paid in education, a tyrannical education carried out in virtual jails. Some might see this as good training, but it all depends on one's personal resolve and family environment, because those schools also turned out most of the criminals that are currently behind bars. That is where they learned to steal, to attack someone with a machete, to cut off an arm if it was necessary to survive. With over 200 people living in cramped conditions, the law of the jungle prevailed, leading to racial conflicts and abuse of power.

Martí was the first to say that children should learn to work the land. On paper it sounded wonderful, but it was carried out for reasons that twisted the whole idea. Now I realize that they were preparing a generation for war. The schools were our adolescent basic training for Angola, for Ethiopia—wars that defined my generation.

I studied civil hydraulic engineering for three years, plus my film studies, and I can count the number of blacks in my classes on one hand. Not because of lack of ability, but because of a social problem They were given access to the schools, but they still lived in marginal districts like they did before the revolution. They went on reproducing old and residual cultural values and patterns that held them back, because there was no social education to go with the academic one. That is why the prison population has such a high percentage of blacks. They haven't been given access to power. The spokespersons for that segment of the population are white.

I left engineering because it just wasn't my thing, and I started studying music.That was one of my sources of conflict with my family: the son of a communist family leaving university. My name is Ernesto because my father was as much of a Guevara supporter as any man could be. Out of curiosity, I have read everything Che ever wrote. I met his father and from that experience, I learned l was not a communist. Since junior high I had been aware of class differences, of the fact that those in power were not exactly of the people. I started writing for a few youth publications, and I met a world of interesting people. I started working at a radio station, and was tired because I started to talk about certain things. Then I saw an opportunity to make the leap to television. I began making films and documentaries using a little hand-wound camera. I enrolled in film school and shot a fictional short on the war in Angola that turned out to be very polemical in Cuba. Afterward I realized I was being kicked out of every place I went, and that the only thing that wasn't giving me trouble were music videos so I stuck to that. I did some fairly interesting work, but what I wanted was to get out of Cuba. I was sick of it, worn down. I had an ulcer and a lot of problems with everybody. I couldn't work.

I came to Mexico in May 1994 on an invitation from the University of Guadalajara. It was the eighth invitation I had received to travel outside Cuba.The government had not allowed me to accept the previous ones, but things changed. They decided to get off the case of all the dissenters and I fell into that category.

A lot of people think the exile of Cuban intellectuals and artists has been a thing of chance, but that's not true. It's a dirty tactic used by Castro and his henchmen to get rid of a thinking part of the population, which could eventually form a serious opposition inside the country.

And so more than three million Cubans wander the planet, bearing the island on our backs, prisoners of nostalgia for a country that was taken from us, dreaming about the salvation of that land that in spite of itself, has managed to have sanctified history, landscape, music and people. Because to he Cuban, whether at the North Pole or in Hong Kong, is still an incredible party.